WGS340 WOMEN & REVOLUTION IN THE MIDDLE EAST

interrogating the misrepresentation of women's & queer resistance in the Middle East

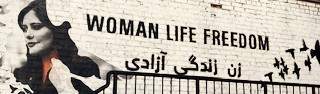

representations of resistance

Toronto, Parliament Street, Cabbagetown

This is the website for WGS340 Women & Revolution in the Middle East (Women & Gender Studies Institute, University of Toronto), an interdisciplinary examination of the critical and creative crosscurrents of gender and sexuality and resistance in the Middle East. Alongside their examination of the histories, memories, political imagination, creative output, and current practices and struggles of feminist and queer movements in the Middle East, students were asked to challenge the simplistic media narratives of the region’s oppression of women and sexual minorities. Like the course’s themes, readings, films, and discussions, this website takes the students of WGS340 “beyond” the classroom, publishing one of their two major assignments-an Op-Ed. The website’s Op-Eds offer readers a thoughtful analysis of the political and social consequences of the (mis)representation of women’s and/or queer resistance in the Middle East. Each Op-Ed investigates the impact of (mis)representation on the lives, activism, and political imagination of women and/or LGBTQ+ peoples in the Middle East.

The West’s portrayal of Syrian women traps them in a narrow narrative of helplessness, ignoring their histories of resistance and revolution. Whether it is on cobblestone streets in Damascus or in tents of refugee camps, Syrian women continue to fight not just for survival, but for autonomy and recognition. To confine them to victimhood is to erase their agency and rewrite their struggle. If the world is willing to acknowledge Ukrainian women as resilient survivors, why does it deny that same sympathy to Syrian women? Challenging these biases is not just about fair journalism. It’s about the reality of resistance itself: how women exercise it, and which women are granted the agency to resist.

Diala About Matar

If misrepresentations of Muslim and Middle Eastern women continue to dominate western media, this will only add to the oversimplification of the complex realities behind gendered struggles and feminist resistance especially in places like Syria. Reducing their identity to the hijab will take away from their experiences of resistance and thus ignore the true repercussions of war on women.

Ruby Atassi

A black and white photograph of an older Syrian woman presents a striking image of a figure standing before a textured stone wall, dressed in a long floral-patterned garment and a kuffiyeh that obscures most of their face. The subject holds a pistol in one hand, raised slightly, while the other grips a larger firearm, possibly a shotgun or rifle. The composition places emphasis on the contrast between the traditional attire and the presence of modern weaponry, creating a visual tension that evokes themes of resistance and defiance. This image invites interpretation not simply as a portrait but as a statement on conflict, and historical continuity. The rough stone wall in the background enhances the starkness of the scene, grounding the subject in a setting that appears weathered and war-torn. Rather than portraying violence directly, the photograph operates through suggestion: placing its subject in a liminal space between tradition and armed struggle, personal resilience and broader political realities.

Abdur Raheem Desai

Sanjay Govindarajan

To some, the Algerian victory against the French in the Algerian Revolution represents one of the proudest moments in the fight against colonialism. To others, it represents the replacement of the French colonial regime with an authoritarian Algerian nation-state. Regardless of the stance one adopts, representations of Algerian women are used to propagate these narratives. While the colonial narrative justifies French atrocities, all forms of representation have an impact on the region, including on the status of women and the struggle for democracy in which many of these women participated. Because of this, when discussing resistance, it is important to center both women and decolonization in order to ensure a just representation of the country’s struggle for freedom.

An image from the Muslim Women Connect website captures three Muslim women of different ethnic backgrounds standing side by side in quiet solidarity, their eyes closed in a shared moment of deep breath and tranquility. The expansive, muted sky behind them mirrors their calm and serene presence. The image offers a counter-narrative to the often tense and conflict-ridden contexts in which Muslim women are typically depicted.

Alexandra Juma

Rather than solely critique these narratives, Essaydi stages her subjects within settings that evoke Orientalist interiors, particularly the imagined harem, but reconfigures them through feminist agency. Through this reconfiguration, she revisits the Orientalist archive not to reproduce it, but to rupture it. Her photographic mise-en-scène invokes history while refusing its terms, foregrounding women who are not passive subjects of a static tradition, but agents engaged in a dynamic re-narration of their own histories. The repetition of aesthetic motifs—script, textile, pose—is not nostalgic, but revisionist: it reworks the very visual language through which empire once claimed knowledge and control.

Suhani Kaur

On 13 November 2023, the Israeli government’s official Twitter account shared a post featuring Yoav Atzmoni, an Israeli soldier who identifies as a member of the LGBTQ+ community, holding a rainbow flag in Gaza. The caption described it as: “The first ever pride flag raised in Gaza,” intending it as a message of hope, peace, and freedom to those living under what they called “Hamas brutality.” Yet when I look at these images, I see something entirely different. Behind Atzmoni, the backdrop filled with military tanks and the ruins of destroyed houses, structures reduced to rubble, remnants of what were once homes, is a stark representation of lives lost.

Tara Kazemi

Captioned “Crowds from all walks of life attend an anti-Shah rally,” the photograph captures five women, veiled and unveiled, linking arms and hands. The women are at the front of a demonstration, marching ahead of several men who make up the photo’s background. They are the face of the protest, united as they lead the crowd through the streets of Tehran. The image presents covered and uncovered women in possession of the same public mobility and autonomy, destabilizing the notion of a male-dominated revolution and a home-bound, oppressed, acquiescent Muslim woman. Burnett complicates Orientalist tropes of Iranian women, which depict them as inherently oppressed and passive, and resituates Iranian women as revolutionary actors.

Chiara Leone

Newsha Tavakolian’s photograph, “Untitled,” from her series Listen dabbles with silence as a tool of resistance. The photo depicts a silent woman dressed all black garments, on her hands a contrasting pair of bright, red boxing gloves. The silent woman stands at the forefront of an empty road, her defiant stance forcing the viewer to confront her person. Tavakolian’s collection originated in response to the literal silencing of Iranian women singers, each photo from the collection being a fantasized CD cover of a woman. Yet, this specific photograph from the collection portrays a woman with her mouth closed – oddly enough, a series titled Listen features a woman with nothing to say. This image demands that we consider alternative modes of resistance—to contemplate the power of silence as a form of resistance to women’s oppression.

Marie Mallare

Yalda Matin

The women in the above photo were leaders who worked, collaborated, and negotiated the means of bettering the status of Iranian women. Confining them to a category of inherently oppressed Third World women erases their dynamic feminist activism and places them as “followers” of Western feminism rather than makers of Iranian feminism. This also prevents an understanding of Iran’s diverse history of feminist movements that have creatively navigated highly politicized gender regimes to resist patriarchal gender norms. The Woman, Life, Freedom movement is both built on and continues this history and must be understood in a way that centers Iranian women as agents of their own feminist histories.

Iranian authorities detained Sepideh Rashnu in June 2022 following the circulation of a video in which a woman confronted her on public transit for defying the Islamic Republic’s compulsory hijab laws. Forced to confess her “crime” of not wearing a hijab on state television, the Islamic regime used Rashnu to punish “disobedient” woman and criminalize feminist activism. However, before being sent to prison, Rashnu staged her own act of defiance. Cutting up what she referred to as “our” crime documents, Rashnu sectioned her hair into three parts and then bound them with rope to represent shackles severed from the body ( “These are my Crime Documents” ). Her use of the word “our” was a clear assertion of feminist solidarity and the right to a woman’s bodily autonomy. By sharing an image of her act on social media, she constructs a visual counter-narrative to encourage critical reflection. Digital platforms shift power to the individual, allowing them to use online spaces to document and oppose oppression.

Sharon Mekhuri

Resistance takes many forms. Some people march in the streets, some people go online, and others, like Sadaf Khadem, enter the boxing ring. Khadem, an Iranian boxer, moved to France to pursue her passion for boxing. On 14 April 2019, she made history as the first Iranian-born woman to compete in and win an official boxing match. This image of Khadem, proudly holding her championship trophy, flexing her hard-trained muscles in her green Iran jersey, captures more than just sporting victory. It is also a political statement, a form of defiance, and a symbol of resistance to the Iranian state’s oppression of women. While Khadem’s boxing challenges the Islamic regime’s deeply ingrained patriarchy, it also challenges America’s persistent misrepresentation of Middle Eastern and Muslim women as oppressed and “in need of saving” (Abu-Lughod 2002). The photo of Khadem is revolutionary as it undermines two oppressive narratives at once: Iran’s legal and cultural restrictions on women in sports and America’s highly selective recognition of Middle Eastern women’s resistance.

Leo Pu

Understanding Fatima and her family’s story is crucial to appreciate the depth and resistance embedded in this piece. Fatima’s home was destroyed by a bomb, injuring her parents, and killing her sister. In the painting, a flower covers Fatima’s eye, symbolizing the injury this attack left on her – the loss of vision in her left eye. Her sleeping posture and closed eyes represent her hope of returning to her home in Salah al-Din and receiving surgery to restore her vision. Fatima’s dreams are a powerful form of resistance, they represent the resilience and determination it takes to have the strength to look beyond the current situation and believe in the possibility of a better future. Envisioning such a future is essential to achieving liberation because it inspires and sustains the drive for justice. Fatima’s Dreams also provides a counter-narrative to the destruction and despair that often define the lives of IDPs.

Emily Ramnauth

Madelyn Stanley

The mural “If you’re reading this Iran is not free,” found in Toronto’s Koreatown challenges simplistic representations of women’s and girls’ resistance in Iran by using alternative and creative forms of defiance. Dominant and narrow understandings of resistance that are prevalent in North America not only limit who we imagine as political actors, but also limit what we imagine as their methods of resistance. Specifically, these representations of resistance often exclude the methods of defiance in which young women engage. This mural in Toronto defies such exclusive understandings of resistance by centering Iranian girls as prominent political actors as they engage in alternative forms of resisting Iran’s oppressive and gendered political regime using social media and dancing. Having this mural in Toronto, Canada’s largest city, exposes several Canadians to these alternative and inclusive representations, raising awareness and allowing for these girls’ to be recognized.

This image of a group of women walking through the streets of Iran may seem like an ordinary portrait of daily life. One woman with her head uncovered raises her fist in solidarity with another woman wearing a hijab, while a third has her hair partially exposed. Yet, this image is more than an everyday interaction – it captures a quiet form of resistance, challenging both state control over women’s bodies and Western misrepresentations of Iranian women. Taken in 2023, it reflects a critical point in Iranian history when women created a space for public defiance against Iran’s hijab mandate.

Shamma Tank

Jena Wouako

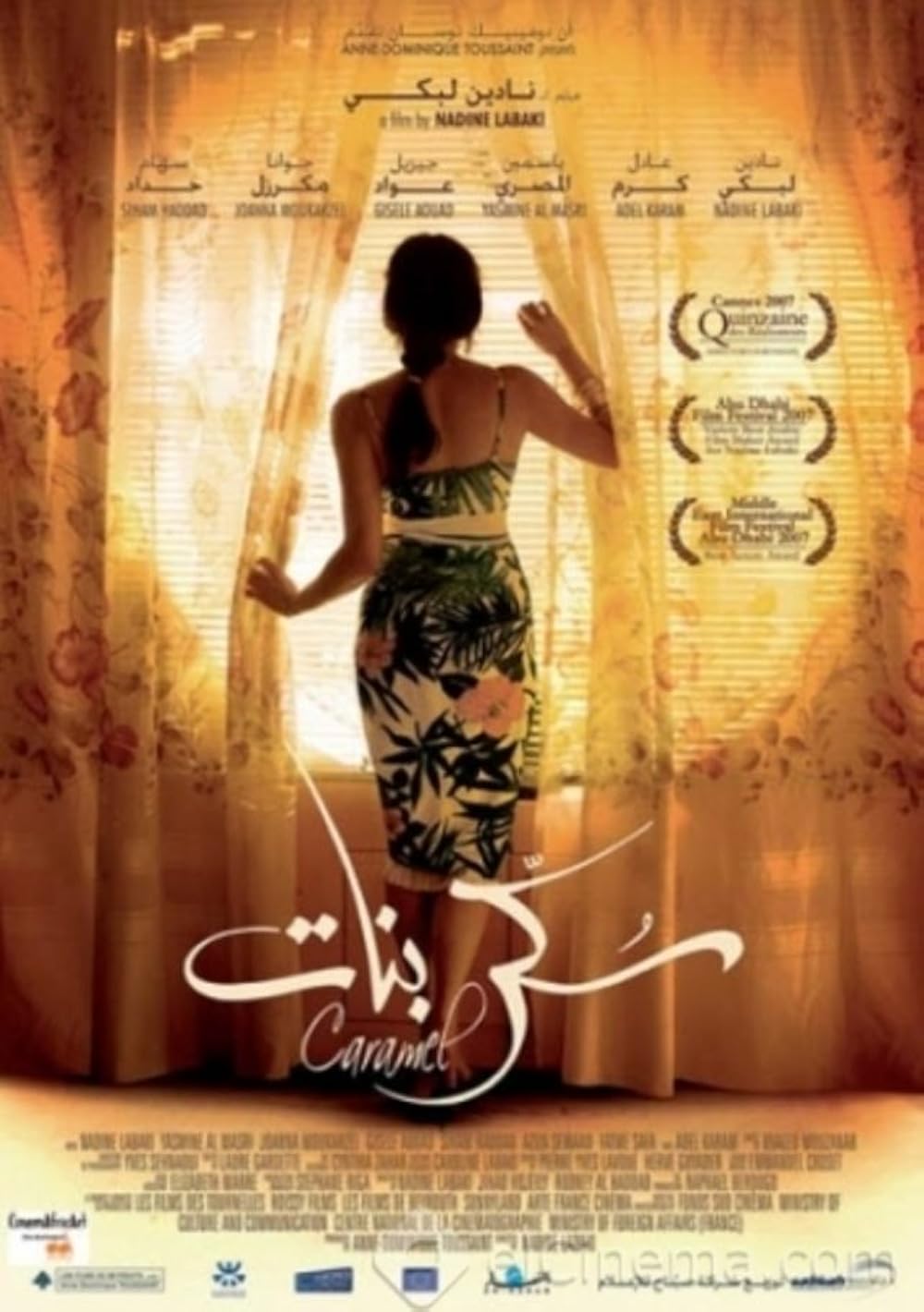

The tale of queer life in the Middle East is one told through a Eurocentric lens, only highlighting persecution. Nadine Labaki’s Caramel (2007) offers a new perspective on Middle Eastern womanhood and queerness from a beauty salon in Beirut. Its ordinariness works to authentically represent the subtlety of Lebanese lesbian resistance, distinguishing it from homonationalist interpretations of queer life in the Middle East. To illustrate Caramel’s exceptionalism, it is imperative to detail the shortcomings of usual portrayals of Middle Eastern queerness. The rare films that tackle queer life in the Middle East often imply an incompatibility between both identities. This is done through portraying Queer Middle Easterners as self-loathing victims, imprisoned by their culture, longing for a life of freedom outside their native country. These narratives are rooted in homonationalist ideas of queerness.