by Suhani Kaur

For centuries, Middle Eastern women have been trapped in the Western imaginary as silent, veiled figures—either exoticized and hypersexualized or cast as victims of their own culture, waiting for rescue (Abu-Lughod 2013). This colonial fantasy persists in contemporary media, where the visibility of Middle Eastern women is dictated by tropes of oppression, religious conservatism, and the absence of agency (Mikdashi 2020; Abu-Lughod 2013). Lalla Essaydi’s work directly resists this violence of representation. Her photography does not merely critique Western misrepresentations; it performs resistance through what Laura Marks conceptualizes as “tactile visuality”—a layered and multisensory aesthetic that engages the text, the body, and the gaze to disrupt the visual regimes of Orientalism (2000). Essaydi’s Les Femmes du Maroc: La Grande Odalisque boldly reclaims both visual and textual authority, strategically destabilizing Orientalist assumptions about gender, spatiality, and power by reconfiguring the familiar conventions of the odalisque.

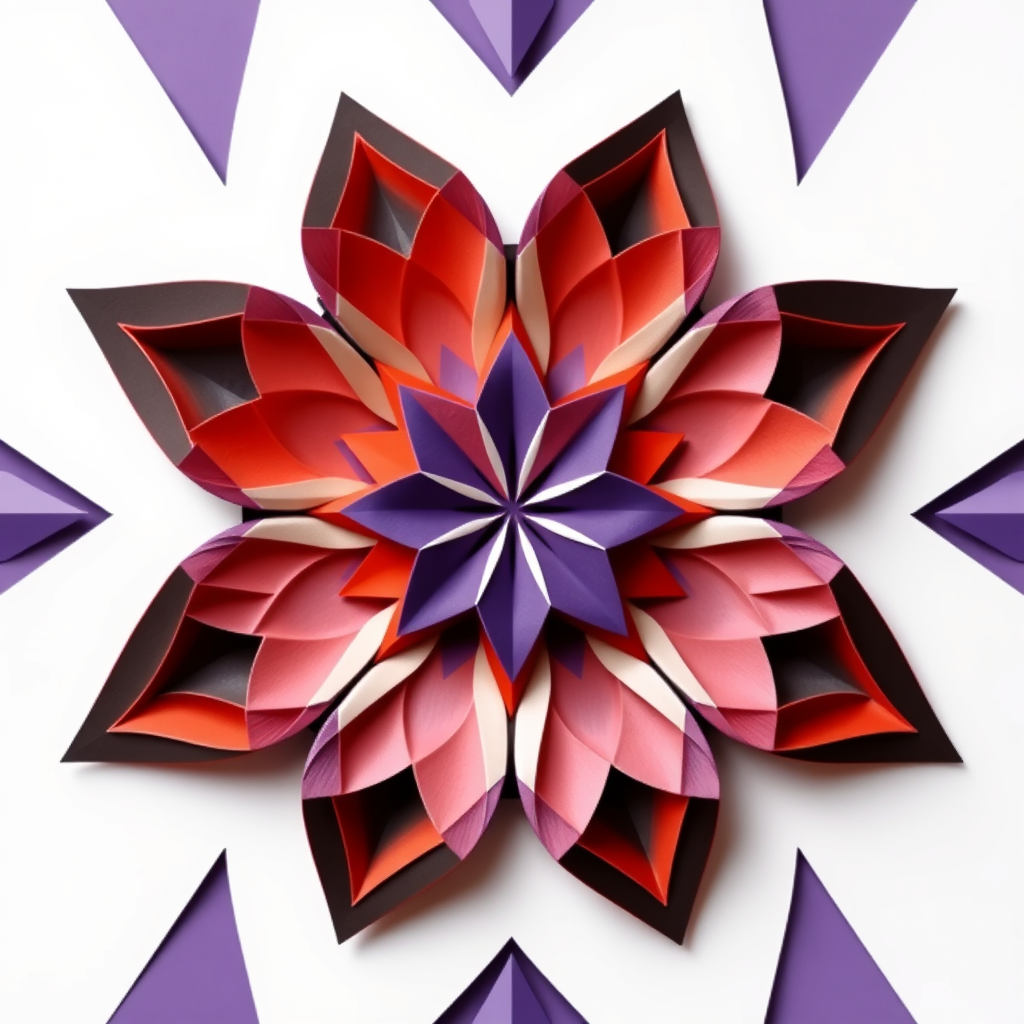

Essaydi’s photograph is a portrait of a woman reclining, her body enveloped in a sea of Arabic calligraphy that spills over her skin, her garments, and the space around her. The script, applied in dark, flowing henna, does not conform to the rigid precision of classical calligraphy (“Artist Statement”); instead, it moves like a living text, breathing across her flesh and fabric, both intricate and disruptive. The subject’s posture recalls the odalisque—a familiar figure from 19th-century European Orientalist paintings, where women were positioned as passive objects of male desire. Yet, in Essaydi’s frame, the pose is one of defiance. Her gaze, neither downcast nor submissive, meets the viewer with a quiet, unreadable intensity. Unlike the languid sensuality and erotic availability encoded in Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’ La Grande Odalisque (1814), this woman resists consumption (Nochlin & Pinder 2002). Her presence is not one of passive invitation but of deliberate refusal.

Text in this image is not simply an adornment—it is a form of authorship. Arabic calligraphy has historically been a male-dominated sphere, associated with religious, legal, and intellectual authority (Dadi 2010). Women’s relationship to the written word, by contrast, has often been policed, their voices excluded from textual traditions. Essaydi reclaims this space by inscribing the female body with language—an act that resists erasure and asserts authorship (Mernissi 1996). The medium of inscription, henna, adds another layer of rebellion. Traditionally used in ceremonial and domestic contexts, particularly during weddings and other rites of passage, henna is a feminine-coded material associated with beauty, festivity, and ornamentation (Marks 2000). By transforming it into a vehicle for text, Essaydi subverts its conventional role, deliberately blurring the boundary between the ornamental and the discursive, the gendered and the generative. In doing so, she reinscribes the gendered division between male (mind) and female (body), challenging the binary that aligns rational authorship with masculinity and the aesthetic or bodily with femininity. The result is a feminist aesthetic that refuses to separate the political from the intimate, the textual from the embodied (Marks 2000).

Beyond its aesthetic and political interventions, Essaydi’s work also engages the temporality of representation, interrogating how the colonial past continues to structure the present. As Lila Abu-Lughod argues, narratives of Muslim women’s oppression have long been instrumentalized to justify imperial agendas—from France’s hijab ban to the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan (2003). Rather than solely critique these narratives, Essaydi stages her subjects within settings that evoke Orientalist interiors, particularly the imagined harem, but reconfigures them through feminist agency. Through this reconfiguration, she revisits the Orientalist archive not to reproduce it, but to rupture it. Her photographic mise-en-scène invokes history while refusing its terms, foregrounding women who are not passive subjects of a static tradition, but agents engaged in a dynamic re-narration of their own histories. The repetition of aesthetic motifs—script, textile, pose—is not nostalgic, but revisionist: it reworks the very visual language through which empire once claimed knowledge and control.

Alongside its contestation of Western misrepresentations, Essaydi’s work also confronts the patriarchal structures within Middle Eastern societies that have long sought to discipline women’s bodies and silence their voices (Ahmed, 1992). Through her use of script and surface, she articulates a double resistance—one that challenges both the colonial gaze and the internalized logics of gendered control upheld by religious, familial, and cultural institutions (Ahmed 1992). By inscribing the female body with text, Essaydi disrupts the mechanisms that have historically confined women to the private sphere, denied them narrative authority, and positioned their visibility as a threat. Crucially, the form this resistance takes is not always dramatic or oppositional in the Western liberal sense. As Saba Mahmood reminds us, agency can emerge in subtle, embodied practices. Essaydi’s visual language embraces this slower, less legible mode of defiance—one inscribed into the everyday textures of life, ritual, and representation (2011).

But perhaps the most radical element of Essaydi’s work is its insistence on opacity. In traditional Orientalist paintings, such as Ingres’s La Grande Odalisque (1814), Middle Eastern women are always available—their bodies, their stories, and their desires are all laid bare for the Western gaze. They are rendered hypervisible yet voiceless. Essaydi unsettles this tradition of display. The text covering the subject’s body denies access, asserting that visibility does not equate to accessibility. The script neither explains nor reveals; instead, it acts as a barrier, shielding rather than exposing. Faced with a surface densely layered in Arabic script, the viewer, particularly one unfamiliar with the language, is confronted with an image that is unreadable, untranslatable, and unknowable. In this way, the spectator is forced to confront their expectations of visibility. What does it mean to look at a Middle Eastern woman and not have immediate access to her meaning? What does it mean for her to refuse legibility on Western terms?

Ultimately, Les Femmes du Maroc: La Grande Odalisque is not just an artistic intervention—it is a political act of reclamation. It demands that we rethink not only how Middle Eastern women are represented, but who controls the terms of that representation. Here, resistance is enacted not through transparency or revelation, but through opacity. By withholding legibility and resisting the visual consumption demanded by Orientalist frameworks, Essaydi writes a counter-narrative; one that operates in a visual language of refusal. She does not simply depict resistance; she enacts it—on her own terms, through a script that denies access.

Suhani Kaur is a fourth-year undergraduate student at the University of Toronto, double majoring in Women and Gender Studies and Sociology. Her research interests lie in global politics of gender, migration, and representation through a decolonial feminist lens, with a focus on how legal frameworks and transnational narratives shape agency, sovereignty, and human rights across the globe.