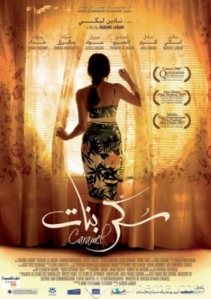

by Jena Wouako

The tale of queer life in the Middle East is one often told through a Eurocentric lens, a lens that focuses on persecution. Nadine Labaki’s film, Caramel (2007), offers a new perspective on Middle Eastern womanhood and queerness from a beauty salon in Beirut. Its ordinariness works to authentically represent the subtlety of Lebanese lesbian resistance, distinguishing it from homonationalist interpretations of queer life in the Middle East. To illustrate Caramel’s exceptionalism, it is imperative to detail the shortcomings of usual portrayals of Middle Eastern queerness. The rare films that tackle queer life in the Middle East often imply an incompatibility between both identities. This is done through portraying Queer Middle Easterners as self-loathing victims, imprisoned by their culture, longing for a life of freedom outside their native country. These narratives are rooted in homonationalist ideas of queerness.

Homonationalism was coined by Jabir Puar to define the practice of fixating on homophobia in the Middle East and positioning the West as a sexual utopia (Raz 2023). According to Puar, homonationalism justifies Western expansion into the Middle East as a humanitarian mission, reiterating colonial notions of an uncivil Third World. The West repeatedly utilizes its film industry to place queer and Arab identities at odds, treating their intersection as comedic or tragic, solely restorable by Western assimilation (Raz 2023). Sex and the City 2 (2010) plays into this trope with Ali, the ridiculed gay Emirati butler of the main white characters. A dramatic rendition of this trope is portrayed in the Israeli film, Out in the Dark (2012), in which Nimer desperately seeks to move to Tel Aviv to escape the homophobia and terrorism of his Palestinian community.

Labaki’s portrayal of Rima, a closeted member of the main friend group, in Caramel defies this trope. Using the intersections of her Lebanese, female and queer identities as forces that complexify her character, without reducing her to a homonationalist cliche. Rima is an outlier in her community. She is masculine presenting and, despite working at a beauty parlor, she has no interest in taking part in aesthetic practices. Innuendos are made about her lackluster love life; her friend Jamale comments “you never like anybody” in the first act. Still, upon the introduction of Rima’s same-sex love interest, Siham, other characters demonstrate discreet excitement for their friend’s newfound romance despite not fully understanding her lack of attraction to men. Labaki demonstrates the tight-knit and loving culture of Lebanon transcends socio-religious norms and gendered expectations.

Rima and Siham’s private scenes take place in the salon’s basement, where Rima sensually washes Siham’s hair. While this basement could be interpreted as a metaphoric closet, this is a Eurocentric understanding of “coming-out”. I would argue that it instead illustrates that queer love in Lebanon remains present in hidden places. Including a queer love story in a female-centered film communicates queer inclusive feminist politics to its audience. Labaki reiterates Maya Makdashi’s argument that studies of gender in the Middle East “must take sexuality into account” (2020). Thus, Labaki sets a new standard for accurate feminist storytelling: the main characters vary in religion, sexual orientation and age, all of which are uniquely impacted by Lebanese culture. These intersections play a vital part in each character’s development. By portraying this, Caramel subverts the narrative that womanhood in the Middle East is monolithic and highlights the importance of intersectionality.

Rima and Siham exchange frustrations and anxieties about gendered expectations. Siham wishes to cut her hair short like Rima but fears her family’s disapproval, a metaphor for the defying Lebanese expectations of hyper-femininity. After letting Rima convince her otherwise, the movie’s last shot depicts Siham looking at her short hair with a prideful smile. Siham’s confidence stems from validation from a newfound community. Labaki’s portrayal of Rima and Siham’s bond differs from Western representations of queer resistance. She showcases that queer resistance in the Middle East places community support and survival over large “coming-outs”, better aligning with the reality of cultural norms in Lebanon. Queer organizations like Meem have likewise proven the value of subtle activism through offering underground support and assistance to queer and questioning Lebanese women (Moussawi 2015). This directorial choice underscores that mechanisms of resistance are dependent on socio-political contexts.

Nadine Labaki’s identity is foundational to this movie’s profound portrayal of intersectionality. As a female director she approached intimate scenes between Rima and Siham beyond eroticized and “male gazey” interpretations of lesbianism (Abdel Karim 2007). Being Lebanese herself, Labaki dedicates the movie “to her city Beirut” and manages to address social issues without falling into colonial tropes, beautifully demonstrating the necessity of representation on screen and behind the scenes to meaningfully achieve liberation.